Singing is healing; especially singing with others, especially outside!

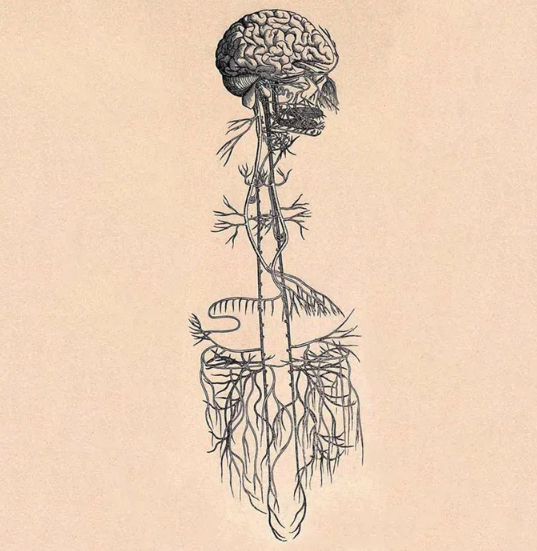

First, let’s get into some of the Polyvagal Theory explaining why singing is so regulating for the nervous system. Deb Dana in her book The Polyvagal Theory in Therapy notes that humming and singing both increase ventral vagal tone. As a primer for those of you new to Polyvagal Theory, the ventral branch of the vagus nerve is the part that serves the social engagement system, meaning the part that responds to cues of connection, curiosity, play, and safety. The other areas of the vagus nerve, which serve the flight/fight and collapsed responses in our nervous systems, are important evolutionary parts of our survival too, but it is key for us to learn how to switch between these various states of shut down, activation, and safety. The more we tone our ventral branch of the vagus nerve, the easier it becomes for us to slide out of states of fear, stress, and depression and into a state of connection and safety.

Singing “exercises the larynx, lungs, heart, and facial muscles, and requires breath control and changes of postures, all of which tone the ventral vagal system,” says Dana, further adding that singing in a group has an added positive effect on vagal tone. Working intentionally with breath control and extended exhalation can block the release of stress hormones and increase immune function.

And then, of course, there is the added therapeutic layer of working with the sound of your own voice, exploring any struggles you might have with speaking your truth, being heard, taking up space, etc. I can certainly say that in exploring voice work with Cara Trezise, a Vermont-based singer/artist/educator extraordinaire, I’ve been able to make progress on my own challenges around judging or withholding my voice. Cara and I have been meeting every so often to explore singing and vocal improvisation outdoors. We will often begin and end with toning together into the forest and being conscious of our intentions. Throughout the session, I become more aware of my capabilities of giving and receiving: paying attention to and letting in the world around me as well as not shying away from giving what I have to offer. At my request we have focused a lot on improvisation; Cara encourages us to do an exercise where we don’t run away from the sounds we make that we think are horrible. If something comes out that we really love or really hate, she invites us to linger there and see how it might transform. When I am frustrated because I am straining to sing higher notes, she encourages me to bend my knees, get closer to the ground, as well as visualize forward and backward into space, and suddenly there is less constriction in my throat as I focus on grounding downwards into the earth and connecting laterally and horizontally rather than trying so hard to reach higher. I let the sounds of the trees and the birds and the heat of the sun influence what might come out of my mouth, and sometimes I wonder if could sing for them, offer them something that might bring them joy of some kind. So I am building relationships with myself, with Cara and her voice, and with the environment as well; these embodied layers of connections make me feel like a real and healthy human being by the end of our meeting. Those who have experienced singing with folks around a fire at night, I’m sure you know the kind of fulfilling connection I am talking about. Resonating reciprocally with others and co-regulating with nature also light up that ventral vagal area in our nervous system.

Through singing we explore range, quality, and texture. What ranges and qualities do we feel most comfortable in? Which ones really stretch us, both in the listening of them and in the creating of them through our voice? Which rhythms can we most easily sink in to? Can we remember the polyrhythms that have enveloped us since our womb days? Singing, like all forms of communication, I think, is so shaped by context and the sounds and types of vibrations we grew up around or spent significant amounts of time around, from humans as well as other creatures and environmental elements. I would expect that climate and geographical biography would have just as much of an influence on one’s voice as does the rhythm of the language they are surrounded by and the melodies of their families’ voices. In my singing explorations, I come to understand my voice both as something uniquely “me” as well as something intertwined with and molded by environment, ancestry, culture. In saying all this, I sense an interesting push and pull between liberation and limitation: which influencing factors do we want/need to peel away in order to reveal deeper authenticity, and which factors are truly integral and helpful to who we are and what we sound like? Just how much choice do we have about our voice?

Singing gives us experiential manifestation of our desires for connection, harmony, beauty, flow, collaboration, play. We hear and are heard, we feel and are felt. It grounds us into our bodies and expands us into our landscape. It tones our vagus nerve so that we become more and more resilient, a quality in high demand for these times.