Patterns of ecological disturbance and succession, and their consideration in the realm of human culture, perception, and movement, has been the topic of much rumination personally and collaboratively over the past year or more. This essay represents a work-in-progress compilation of vignettes which may later be edited more thoroughly and/or expanded into a longer project.

________

Succession Ecology: Patterns of change in the species composition of a given place, in relationship to the changing overall context and conditions.

String together the snapshots in time of a plot of previously bare soil. Observe the changes from weedy/ruderal/annual plants to brambles to saplings to thickets to forests. Consider all that is invisible to the bare eye, all the changes in microbial and fungal communities in the soil, all the animal companions inhabiting, using, and changing the places as they change. String together the snapshots in time of a place through the geological scales of epochs, eons, eras, through glaciers, topographical uplifts and river meanders, entire species born and gone–what makes a place a place, throughout so much change?

The “climax community” concept, the supposed final end goal of the successional process (often imagined as a “perfect” old growth forest), is an outdated myth. Nothing is static and nothing is alone; disturbance and fluctuation are woven into the fabric of life on this planet.

Landscapes have adapted to all sorts of disturbances. Cyclical and controlled burning, non-human and human mammals grazing/harvesting/compacting/making homes/etc., flooding/wind destruction/eruptions, and other earth-moving and impactful events all disturb the every-day life of a place. What are the different nuances and trajectories of a place after a given disturbance event? What are the rhythms and tempos of change in the wake? What are the choreographies of the bodies involved in disturbance events, whether on the doing or receiving end, whether single bodies or collectives of bodies making up a larger body? From which scales of perspective do we perceive and move? Who are the performers in the Dance of Disturbance, and do they know the steps–how many times has this dance been danced, and how has it morphed over time?

“All organisms make ecological living places, altering earth, air, and water. Without the ability to make workable living arrangements, species would die out. In the process, each organism changes everyone’s world. Bacteria made our oxygen atmosphere and plants help maintain it. Plants live on land because fungi made soil by digesting rocks. As these examples suggest, world-making projects can overlap, allowing room for more than one species. Humans, too, have always been involved in multi-species world-making.

…Ways of being are emergent effects of encounters. {Species} assemblages don’t just gather lifeways, they make them. Thinking through assemblages urges us to ask: how do gatherings sometimes become happenings–that is, greater than the sum of their parts?”

-Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World

Disturbances often involve death. But they are also portals of possibility, change, interruption. Like a beaver felling trees and creating distinct wetlands where there previously were none, your actions open pathways of ecological trajectories. A death here creates an opportunity for a different kind of life there. Involvement orients a path; suppression of involvement orients a different path. Everyone co-creates a place. As large mammals with large scale technologies, we humans have a large impact; our paths are broad, wherever they go.

Walnut Creek

In Walnut Creek Park, an unintentional fire burned maybe 6 years ago. There’s a bridge there that I especially love, crossing a wetland in the forest. One on side you see mature Mountain Laurel, tall, curvaceous, creating a thick shade on the ground. On the other side, you see the burned Mountain Laurel, still short, lots of dense sprouts remerging thick and straight from the base, and lots of native grasses along the edges of the trail and in pockets about the Mountain Laurels.

Imagine yourself standing on this bridge. Face the burned area for a moment. Inhale spaciousness, the charred logs, the rust colored Broomsedge and Little Bluestem foliage interspersed among mounds of evergreen. Exhale and create a gesture. Slowly turn around to face the unburned area. Walk a few paces, very slowly, to the other end of the bridge, and with each step, allow the gesture to change, fall away, or develop further. What is the new gesture you embody at the other end of the bridge? Then let it dissolve. Go to the middle of the bridge and imagine what occurred when the fire met the wet earth and stagnant water. Dance that.

_ _ _ _ _

Liminal Lots

In the rubble and ruins of Staunton Mall, still being deconstructed, Mustards, Pokeweeds, Tree of Heaven, and many others grow in the cracks in the concrete and among clusters of frayed electrical wires poking out of trash. In gaping holes in the ground, you see a mat of roots dwelling under the surface of the lot. What would sprout again one day if given the chance? What would grow if given long enough to move through the phases of succession again? How long does a viable seed last in the seedbank, anyway?

This mall lot was once a prairie. Long before that it was under salt water.

A landscaping client wants me to remove all the Pokeweed in her garden. A different landscaping client wants to plant Pokeweed in her back yard.

“The mall has always been a temporary monster, built upon the falsity of forever materials, anti-aging campaigns, performances of identity, and consumption without regeneration. But when the halls of the garish mall gods are upturned by another generation’s monsters, the subterranean cultures are ever-present. The bulldozer and excavator might be contracted to usher in another installment of consumption, but they have also opened a portal into the grief of transformation, and the stories of multi-species possibilities.

Crawling and clawing through one mall’s rubble remains are whispering cinder blocks, angled rebar, and tangles of upended upholstery that croon conversations with annually germinating seeds, wild geese, street light/full moon bioluminescence, and vernal pools. How are we transported into alternative paradigms of community care by noticing and paying attention to these feral and emergent interactions?” -from the show statement by Taylor Hanigosky and Liminal Lot for “Memorial for the Staunton Mall,” a curated art show centered on the demolition and nostalgia of a town mall. Liminal Lot is a series of place-based participatory performance experiments conducted by a group of local artists in partnership with several sites of ecological transition in Virginia.

_ _ _ _ _

Barrens and Hellstrips

Rocky outcrop barrens ecosystems are full of plants adapted to the harshest of environmental conditions. They find their homes in small amounts of soil, growing in cracks and crevices on the swathes of bedrock. They are exposed to intense sunlight and high winds. Rainwater runs off quickly. Trees are often stunted despite their age. Early successional trees like Juniperus virginiana (Eastern Redcedar) which usually get shaded out by canopy species elsewhere in the woods and become leggy and short-lived, in the barrens ecosystem grow wide, old, and laden with berries. Grasses like Danthonia spicata (Poverty Oat Grass) and Schizachyrium scoparium (Little Bluestem) form a thick lawn between the rocks. Stonecrops, mosses, lichens, and Prickly Pear cacti call these barrens home, thriving on the eroding rock faces and thin soils.

Annual/biennial Appalachian Phacelia in pretty pale blue clumps everywhere catch my eye. I recall another time I saw this plant growing densely in a dappled woods in a campground where the forest and soils had clearly been pretty degraded. Non-native hardy generalist species abounded, opportunistically doing their work of creating biomass in difficult early successional conditions. Phacelia was one of the few endemic species present, growing thickly alongside the other vanguard plants.

Barrens-adapted plants are often chosen for enlivening so-called “hellstrips” in urban landscaping projects- small beds within parking lots or between sidewalk and street where not much can be coaxed to grow. That is, not much that is deemed appropriate by the standards of conventional landscaping. Bittersweet, Kudzu, Lespedeza, and Ailanthus, for example, can also thrive in the hellstrips, but because of their non-native status are often the target of extirpation.

Barrens assemblages have adapted to harsh conditions in similar ways that the non-native plants demonized in the urban landscapes are adapted to harsh conditions of other sorts. Excavation, soil compaction, strange pollution, heat island effects, and other pressures exert themselves on the urban ecosystem. Like the native plants of the ridgeline barrens, the constellation of non-native species that persist in cracks in the pavement, between civic-minded applications of herbicide, are adapting to this early stage of succession, in the places and times where crumbling concrete becomes a forest.

Choreograph a life of making do with less. Rehearse now for that future. We are already rehearsing, bodies diseased by plastics, toxins, endocrine disruptors, new viruses, the cancer of finance capital; harshness increasing, will our bodies and minds adapt? We are already rehearsing, bodies turning towards neighbors and making gardens.

_ _ _ _ _

Disaster Taxa

Localized extinction events occur all the time. Imagine: an area of diverse habitat, a mesic oak-hickory forest, say, tenanted by salamanders and mayapples, watered by many little creeks, deep in quietly mouldering leaf duff, is slated for development, whether for exurban subdivision, military supplies manufacturing, or some other function essential to progress, civilization, etc. Heavy machinery rumbles in, shreds, crushes, and rips out every visible green plant, pulps the salamanders, backfills the creeks, compacts the soil, inflicts insoluble erosion problems, and then is put to work making the place fit for human commerce. Later, if non-native early successional Lespedeza or Autumn Olive take root in this difficult landscape of recent localized extinction, people are heard to exclaim, ‘how terrible, these “invasive” plants, destroying biodiversity, taking over and displacing our native plants!’

Cities are ecological disasters. I think of all the roads and highways, strips of localized extinction events stretching in all directions. And all the roadkill. A murder zone of speeding vehicles {fueled by greedily excavated millions-of-years-old plant and animal bodies} bisecting what was once a contiguous swath of home for someone. Not to mention all the salt, pollution, etc. The Ailanthus, Mimosa, and Kudzu lining the highways and hellstrips? Maybe they are a form of ‘disaster taxa,’ those pioneer organisms able to take root and live in the wake of catastrophic disturbance events. Perhaps these hardy newcomers will be the ones to weather the ongoing ecological storms?

Some people think we ought to spray all non-native species with toxic chemicals until they no longer offend our roadside sensibilities, and replace them with the “right” sort of plants that are “supposed” to be there. The saturation of highly compacted soils prone to erosive runoff with carcinogenic chemicals is a small price to pay for extirpating these noxious weeds, right? Information about which kinds of plants are right for a place and which kinds are wrong is common knowledge, after all, and the sources and proponents of that knowledge have proven themselves trustworthy, right?

Fragment yourself irrevocably

But stay the same

“As unstable as species-poor ecosystems may be, they are preferable to the sorts of species-poorer landscapes that result from the extirpation of all those organisms that stand a chance of enduring as disaster taxa.” –Ben Kessler, Rivers of Wind: Reflections on Nature and Language

_ _ _ _ _

Novel Plant Communities & Remediation

On the rocky slopes up towards the ridgeline, there lives a community characterized by Pawpaw, Tree of Heaven, and Blue Cohosh. We call it the Pawpaw Jungle. There are also some Hickories and a variety of other native plants. Tree of Heaven can be an indicator of repeatedly and sometimes harshly human-disturbed soil, and what you would expect in an early successional woods in this area. Blue Cohosh cannot live without microbial symbionts that thrive in older, richer, undisturbed soils. The seemingly mutual coexistence of native and non-native species makes us wonder about the novelty of this plant community, how it came to be this way and how it might change in the future. Belonging is a process of “naturalization” and merging with a place over time. Species assemblages are not fixed.

Along the South River with Taylor, we find a community of native Horsetail (Equisetum), Sochan (Rudbeckia laciniata), Hearts-a-Burstin’ (Euonymus americana), Blue Bells (Mertensia virginica), Spring Beauty (Claytonia virginica), and non-native Multi-flora Rose (Rosa multiflora), Garlic Mustard (Alliara petiolata), and Honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica). They seem to have formed a stable ecological community. This occurs outside of the zone of officially designated “ecological restoration.” Inside the zone, local plants, native and otherwise, have been extirpated, and plants from nurseries from who knows where were planted instead. New species were selected that, theoretically, might grow there when the place is past an early successional stage- nevermind the fact that the place is in an early successional stage, nevermind the history of toxic pollution being dumped into the river here further altering the successional pattern from a ‘natural’ baseline. I wonder where all the mercury-laden topsoil scraped off the earth (that was in the process of being remediated by local Mustards and other hardy generalists) was transported. How long does a poison linger in the soil and how do the bodies of beings like fungi, plants, and bacteria digest and change it?

Vultures are, to me, heroic birds. I love them for their ability to digest, cleanse, and effectively neutralize any diseases a corpse had been infected with. When I learned that they also hiss and utilize projectile vomiting of their stomach acids for self defense, I loved them even more. Visualizing myself hissing and spewing vulture vomit in certain situations has proved to be a valuable coping mechanism. The broader capacity to metabolize and transform sickness- of a culture, for instance- as well as the capacity to spew acidic bile when necessary, are crucial components in the dance of disturbance and possibility in these troubled times.

Where are the places of poison in your body, mind, and spirit? What poisons do we swim in without realizing it anymore? How have the poisons shaped our attitudes, embodiment, feelings, and how we show up for others? Where are places of death in body and psyche that need assistance in their decomposition, digestion, and transformation?

As you contemplate cultural “poison” or “pathogen,” create a gesture of that being or essence. Then swallow that gesture and let it ferment inside of you. What is the new gesture? Swallow it and let it ferment inside of you. What is the new gesture? Continue until the gesture bears no resemblance to the original movement. (This is my spin on an exercise from the Shadowbody Butoh Manual)

What is an artifact of a cultural “toxin” or “disease” that exists in your home community? How can you interact with this object in an embodied way so as to deconstruct, decompose, re-purpose, or otherwise transform the relic, whether materially or spiritually or both? {See Meesha Goldberg’s “Empire is Over” for inspiration}

_ _ _ _ _

Pond Communication

As the pond fills up over time with leaf debris and sediment, it becomes shallower and shallower. The channels leading to it silt up, the check dams come undone, and the water finds another path through a hill to a nearby creek, where it would go anyway but for the dugout spillway into the pond. I decide to arrest the natural succession of the waterway, preserving the pond’s useful habitat for frogs, newts, herons, and others. I re-dig the channels, fix the rock structures to catch excess sediment, and move the silt that has already accumulated elsewhere. I carve pathways in the thick muck for the water to flow through the Sedges, Elderberry, Lobelia, and Wapato and to rejoin the pond once again.

You are carving through muck, sinking into muck, losing your boots in the squelch, you are moving heavy shovel-fuls of wet pebbles; you are water redirecting into newly opened channels; you are observing feedback: each carve makes a change, the water communicates clearly.

_ _ _ _ _

Ashes Falling Down

Ash trees everywhere in the woods and seep swamp are falling down. Their death some years before was the work of superabundant populations of non-native Emerald Ash Borer beetles. The dead Ashes linger for a time as standing snags, then succumb to gravity piece by piece.

When the Ash trees fall, they bring down heaps of vines (especially Grapevines, Greenbrier, and Bittersweet) and limbs from nearby trees, too. Shrubs and forbs get smashed, pockets of light open up. There is opportunity in this death-opening, but which trajectory will prevail? A trajectory of increased vinescape? Ashes resprouting as shrubby understory? Other tree seedlings finding the light they need to finally thrive?

Coming home one day, I noticed a very close Ash tree had finally fallen, bringing with it Sycamore and Mimosa limbs, nearly smashing a baby Pawpaw I planted last fall. I wanted to clean it up right away, make it tidy, get limbs out of the creek, reorganize the chaotic Grapevines half pulled down. I see it staring at me every morning from the window. Eventually I’ll sharpen the saw blades and get to it. Of course, this sort of tangled treefall happens all the time further upslope in the seep swamp and elsewhere in the woods. Here feels different. I’ve spent days tending the dams on the creek, adding new plant stock to the water’s edge, actively tending this zone near my dwelling place.

Snags caught and suspended by vines high in the air increase the susceptibility of the forest to crowning wildfire. High kindling, drying in the breezes of another drouthy spring. Ash snags and ice storms have left an abundance of dead wood everywhere. The lack of prescribed fire and ongoing tending at the scale needed in this place creates potential for future hazard.

Ashes, ashes, they all fall down

Let one limb fall

Let your whole trunk fall

What’s different if you’re tangled in a vine, suspended in a net above the ground?

Feel the future in the present, what future do your falls fuel?

_ _ _ _ _

Mapping Trajectories

Think of an event that has radically altered the trajectory of your entire life. What is the gesture that embodies the nature of that disturbance? Create a map of aftermath possibilities: the direction you actually went in, and all the other possible paths that opened up in the wake of that disturbance event.

Think of an event that has radically altered the trajectory of your family. Repeat the above: What is the gesture? What is the map of aftermath possibilities?

Do the same with an event that has radically altered the trajectory of a place you know well; and the same with the trajectory of a nation or other political entity.

_ _ _ _ _

Bittersweet and Mutual Benefits

Oh, Bittersweet. Bitter and sweet you are indeed.

Celastrus orbiculatus.

Prior to last fall, I was mostly standing up for you, blinding myself to any potential harms you may cause. It was, perhaps, mostly as an abreaction to the spewing hatred from strict conservationists and native plant purists. At the same time, I hadn’t really been interested in getting to know you the way I would with certain native or medicinal plants. I wasn’t open to doing plant meditations/journeys/listening to what you may have to share on a deeper level. This was probably because I had indeed internalized the idea that you were lesser-than, not helpful, a nuisance, an outsider, etc. I would not succumb to consciously vilifying you or promoting your extirpation, but there was a distance. I did, however, feel fine about cutting back your vines and using them to make wreaths and other crafts.

When I finally did get around to sitting with you and opening the possibility for connection, you pointed out a few things to me: your connection with the “inbreath” – an inhale of preparation and gathering energy, a strong upward propulsion of growth and mass; the way your bright orange roots spread so rapidly and bond with certain arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (characteristic of young soils); a nudge to meander and observe the variations in vine behaviors across the forest. The experience brought shape and shading to my sight, the blindness was, perhaps, healing. Along with noticing your sense of emergency-mode biomass creation and admiring your power and texture, I really began to notice your girdling capacities, observing the deep squeezing indentations you created in trees. It is different than the Greenbrier, Grapevine, and Poison Ivy. The security of the verdant future you create comes at the detriment of seedling canopy trees, and their portended future forest. I’m not sure I’ll ever have a goal to extirpate you completely from this forest, but I have fewer qualms now thinning you out in the service of nearby trees who prefer not to be girdled; I’d like to carve space for an ecological trajectory that includes genetically resilient populations of longer term “native” plants of this place. I know you are thriving in part because of the disturbance events here- the logging roads, livestock paddocks, and the displacement of Monacan people and their methods of caring for land. I will continue to cut your vines, making use of them whenever possible, and probably also digging up some smaller vines, mindful about how bioturbation affects the balance of organisms within the soil, mindful of the successional dynamics of the place.

The work of tending through small-scale disturbance provides feedback quicker than I expected. I’ve created small paths and trails through a thickety part of the woods. Simply cutting back some Privet and Multiflora Rose here and there, bringing down dead snags, and thinning native but overabundant Spicebush where appropriate, has clearly been favorable for local populations of Black Cohosh, Stoneroot, Snakeroot, and Pawpaw. Right along the trails that I have cleared and added wood ash and day-old herbal tea remains to, these native plants are coming up very lushly and happily. This is despite the presence of Garlic Mustard and Tree of Heaven in that area, non-native species maligned for their putative allelopathic properties. Allelopathy describes the ability of some plants to suppress the growth of other plants in their vicinity, reducing competition. Beeches and Walnuts are famously allelopathic. Whatever allelopathic compounds Tree of Heaven and Garlic Mustard are alleged to contain, as touted by “invasives fact-sheets” and other propaganda, it really must not be that significant, given what I’ve observed with my own two eyes. The opening in the shrub layer provided by cutting and tending on a regular basis, perhaps combined with input of organic materials otherwise deemed waste (tea herbs and wood ash) seems to improve the conditions for the native plant population here. This is mutually beneficial: I enjoy the paths that allow me to travel easefully through an otherwise thickety area, and the plants are providing excellent feedback about this strategy.

As climate changed during the Pleistocene and Holocene, many plants and animals had to be invasive to adapt and shifted their endemic range (Webber and Scott, 2012). For instance, several North American taxa (Alnus, Quercus) appeared in the Andes after the Pliocene joining of North America and subsequent Pleistocene cooling (Hooghiemstra and Sarmiento, 1991). Glaciated regions of North America were colonized by invasive species following late Wisconsinan ice retreat (Davis, 1976). With such a perspective in mind, it should be no surprise that they are doing the same in the Anthropocene. The question then becomes how land managers and policy makers plan for these processes, judging the positive and negative roles that invaders might play, and deciding between priorities such as the maintenance of ecosystem services or the preservation of native species (Lawler and Olden, 2011). Policies must recognize this long-term non-fixity in nature, the agency of plants and animals themselves, and the high potential for surprise and unexpected outcomes. – Jacques Tassin and Christian Kull, Facing the Broader Dimensions of Biological Invasions

_ _ _ _ _

Weeds and Relics

“Weeds love disturbance and (most) humans love to disturb. And thus, humans and weeds share a long, intertwined history. For anyone who has ever turned the soil, weeds are our ancestry and our inheritance…many disparaging words have been written against this branch of our family. Weeds have been blamed for working against the goals of food production, for stealing resources from more-deserving plants, for growing too far, too fast, and without discernment. Yet, their wild bodies are filled with food and medicine. They show up as first responders when land is turned up-side down and stitch the soil back together again. They feed pollinators and protect waters when other plants cannot.”

– Tusha Yakovleva, Edible Weeds on Farms

In the garden, as we weed and prep our beds each year, familiar hardy guests arrive with no coddling or effort from us, and despite much weeding of them the previous year: Violets, Chickweed, Plantain, Dandelion, Lambs Quarters, Fleabane, Wingstem, Deadnettle. Some we use for food, some we weed out, but they always come back. One of the beds over the winter we let become a solid mat of chickweed, providing some effortless nibbles of fresh green throughout the season. We must disturb the ground to prep the soil for our annual vegetables, so the area is never allowed to move beyond a certain successional stage.

Every contact leaves a trace, every movement an imprint. Tracking the turkey and coyote scat, the neighborhood dog prints, the hawk’s rabbit kill, the squirrel’s acorn shells, the bear bones, the deer scrapes, the soft feathers, the ants farming their aphids, we get a glimpse of inhabitation, lifestyle, and psyche. I always wonder what the other creatures think of the human tracks and signs, the prints and relics of participation we leave, both material and spiritual, and what they say about our psyches; which signs are codified into meaning and which might they puzzle over?

Sit in stillness, quiet the chatter of species narcissism, diminish the space of self and listen in all directions, dissolving into place; as your zone of disturbance diminishes, the birds’ alarm calls settle, they go about their singing and foraging. Feel the direction of the water and wind, let the shields around your heart soften into a receptive state. Is there a way to dance with the place quietly, dance freely, yet not alarming the birds or disrupting? What is the balance of “taking up space” and selfhood with respect and moderation? There’s a time and place for tilling, shouting, running, skidding through the mud, smashing rocks into one another. Today, though, I dance quietly.

_ _ _ _ _

Thinning

Elsewhere in the woods, where a young Tulip Poplar stand has gotten too dense, and where the Morels used to come up (but no more) we cause disturbance by thinning the Tulip Poplars. A death for some of the trees, it may be an opening for more life for the Morels, and perhaps this area may once again become a prairie or edge-meadow community. We find remnant populations of native Mountain Mints and Monardas that point us in that direction. We listen for feedback, as this landscape tells us what it would like from us.

_ _ _ _ _

Liminal Lots, Again

In one of the liminal lots on a mountain-top near a half-abandoned hotel, we listen for stories. Though we know some history of travel, of dangerous and fatal jobs, of railroad, carving, wind, war, fog, tourism, fire, in this place, for this session we focus on trusting the body to hear the stories we may not consciously remember. Of course I’m also listening to the plant community currently thriving here: Virginia Creeper, Bittersweet, Poison Ivy, Black Locust, Sumac. Early successional patterns. And the Quince and the Catnip, relics of recent human ornamentation. The wind has brought down more limbs since last time we were here, and many saplings lean heavily under the pressure of wind and vines. Vines envelop the derelict buildings nearby, crawling through shattered windows. Shards of glass and ceramic dot the lot, plus trashcans and some old underwear. At some point I turn off the logical labeling aspect of mind and allow movements and gestures to emerge, body resonating, imagining, remembering, in the language of temporality and space. Our group researches for a while, shares movements, creates combinations, follows surprising threads and juxtapositions. I find it challenging to translate the movements into words, for it’s a language of its own. As always, the Vultures join in.

_ _ _ _ _

Eclipse

A few minutes before the eclipse, a Peregrine Falcon flies Northwards. In the moment of the eclipse, the sun becomes the moon. We are in the liminal zone, a blink, a page turning, a world between worlds. Everything is still and quiet, the creatures cease their singing and moving. When the sun is reborn, is it the same sun or a new sun, a new day? Was this just a pause or a shift of trajectory? Another Peregrine Falcon flies Northwards.

_ _ _ _ _

Olive Groves and Dabke

“David Boyd, the UN special rapporteur for human rights and the environment, said: ‘This research helps us understand the immense magnitude of military emissions – from preparing for war, carrying out war and rebuilding after war. Armed conflict pushes humanity even closer to the precipice of climate catastrophe, and is an idiotic way to spend our shrinking carbon budget.’ –Emissions from Israel’s war in Gaza have ‘immense’ effect on climate catastrophe, by Nina Lakhani

Ecological and humanitarian catastrophes often go hand in hand. Genocide and ecocide must be met with disruption and demand for an end. Like the most resilient of plants in harsh conditions, people who settler colonialism attempts to erase learn how to strategize and survive. The embodiment and choreographies of protest take many forms. Creative, therapeutic, and ecological practices cannot be separated from material and political conditions in which they arise or are enacted. Solidarity is an international dance, it’s only in that collective struggle that we have a fighting chance.

“These olive trees are much more than a crop: they are symbolic of Palestinians’ long-standing rootedness in the land. Olive groves have often been passed down through families.

…They are emblems of strength and resilience: they are extremely drought resistant and are able to withstand some of the harshest growing conditions on Earth. Many olive trees date back to centuries before the Israeli occupation.

…The devastation of olive groves and other farmland has been described as the ‘environmental Nakba’ by scientist and author Mazin B. Qumsiyeh, writing in Science for the People magazine, Volume 21, Science Under Occupation. Nakba, translated into English as ‘catastrophe’, refers to the 1948 displacement of Palestinians.

… “Israel’s colonial settlements have had a devastating impact on the Palestinian environment and on indigenous Palestinian lives,” Qumsiyeh writes. “This raises significant questions about the possibility of sustainable development under occupation.” – Yasmin Dahnoun, The ‘Environmental Nakba’

“Shortly after the development of jewish Israeli Dabke, many Palestinians decided that they needed to find ways to perform their dabke dances in order to avoid cultural erasure. They continued to practise the dances in the circle formation within community settings, but many Palestinians also began to perform the dances in costumes, facing forward on proscenium stages for regional and international audiences. For these performers, the dance shifted from a social form to a means of communicating resistance to occupation and cultural obliteration.

…Through these examples of cultural appropriation, cultural erasure, white washing, and power dynamics that preclude Palestinians from pursuing a purely physical experience in their dancing, and demonstrate their lack of resources for their training, networking, and touring, we can extrapolate how any embodied practice, whether performed on the stage, or in the studio, can never be neutral or outside of a cultural context.” -Nicole Bindler, Palestinian Dance and the Obfuscation of Somatic Source Material

_ _ _ _ _

Fire and Flood, Displacement, and “Invasive Ideologies”

“Some scientists now argue that the wildfires are more severe and occur on a larger scale than the wildland fires in aboriginal times and that therefore the wildland ecosystems are also at risk. N.C. Johnson states: ‘The lesson here is that sudden departures from long-established human-ecological interactions can lead to yet another ecological transformation.’ … Today in most ecology and conservation biology books and articles, disturbance is still defined as natural or created by modern humans—without a separate detailed distinction of indigenous disturbances. Why should one make this distinction? Because Indian manipulations may have occurred long enough in an area to be considered part of the normal environment of a vegetation type. The disturbance regime descriptors in some cases were different enough from the natural disturbance pattern to create new pathways of vegetation change and ecosystem development. Ecological effects from indigenous burning might register at every level of biological organization from the organismal to the landscape scale.” – M. Kat Anderson, Introduction to Omer C. Stewart’s Forgotten Fires

Controlled fire keeps the forest in a mid-successional open state, favoring the development of keystone species such as Oaks. Thousands of species co-evolved with this disturbance regime and the now-keystone species it favors. Colonial settlers displace the indigenous peoples of this place and implement different and alien approaches to land use and land ethic. What happens when there is a disturbance of the effective disturbance pattern?

Low-grade fires that stay close to the ground have a cleansing and opening effect on the land. While death still occurs, many tree trunks and roots stay intact, and the soil is enriched by the ashes from the burnt debris. Certain plant and animal communities are adapted to fire. They thrive with its presence and diminish when fire is suppressed. Some plants even require the presence of fire to reproduce: “Table Mountain pine cones are the only species in the Blue Ridge that requires heat to release seed. Heat as low as 90 F melts the resin that keeps cones closed so seeds fall about two minutes after fire passes, which provides the advantage of falling on nearly bare ground.” (J. Adam Warwick, The Fire Manager’s Guide to Blue Ridge Ecozones).

As we know from watching Canada, Australia, Borneo, California burn, certain high-intensity fires can be catastrophic. They not only burn away the tree canopy, but perhaps more concerningly, their scorching can kill soil microorganisms, and imperil dormant seeds. With roots and soil deeply disturbed, the stage is set for a feedback loop of erosion and continuing depletion.

Coupled with the increasing volatility of the climate and projections of more intense droughts and floods, extremity is in the cards.

Would you resist an invitation to embody a choreography of extremity? To resonate with a quickening feedback loop of wildfire, erosion, and flood? Would you rather embody a dance of ease, gentleness, and rest? What would you do if asked to jump on one leg for 30 minutes straight with no stopping, and if you fail to complete the task, the consequences are dire? What will you do when your muscles are trembling, when more and more involuntary twitches and gestures emerge, because exhaustion has worn away your barriers to all that has been stuffed into the unconscious realm? Do you gravitate to the movement classes that encourage you to rest and not push yourself out of your comfort zone, or do you gravitate to the training forms that push you beyond what you thought you were capable of? Is the choice to rest, nap, and relax a privilege when so many do not have that choice right now? Is there a way to sit in the fire and not scream? Is it too late for balance?

Hush, rest, regain your equilibrium.

“We are at a critical juncture in applied environmental sciences, where Indigenous knowledge (traditional ecological knowledge or TEK, etc.) is finally, thanks to Indigenous leaders, Elders, and knowledge holders, being recognized. However, this recognition comes with important warnings regarding the superficial applications of that knowledge, misappropriations of the knowledge and unreal expectations (Wildcat, 2010; Campion et al., 2023). The reality of “academic gaslighting” where Indigenous knowledges have been coercively and actively suppressed for over a century but are now being summoned by the same institutions that tried to erase them, causes measurable harm (Geniusz, 2022).” – Jennifer Grenz and Chelsea Geralda Armstrong, Pop-up restoration in colonial contexts: applying an indigenous food systems lens to ecological restoration

“Our Anishnaabe collaborators reframed problems of environmental change as related to the introduction of a Euro-American land ethic. Our interviews revealed specific linkages to European settlement, but not to simple timelines associated with post-contact biotic loss and change. Instead, according to Anishnaabe teachings, culpability lies in “invasive” ideologies rather than the fault of specific animals or plants.” -Nicholas Reo and Laura Ogden, Anishnaabe Aki: an indigenous perspective on the global threat of invasive species

“As Native, feminist scholar Lindsey Schneider (Turtle Mountain Chippewa) describes,

“‘Land back’ […] should be understood not as the return of title but rather as the full restoration of Indigenous land relationships. Title acquisition may indeed be part of the process, but cannot be its entirety. It is only through the restoration and flourishing of the complex web of Indigenous relationships with land, water, and our more-than-human-kin that we can hope to recover from the damage that settler colonial notions of land-as-property— with all their attendant conceptions of gender, heteropatriarchy, and domination— have done to the land and Indigenous peoples.”

Indeed, “land back” is a powerful ecosomatic practice that helps to ensure that the exemplary ecosomatic practices of Native peoples persist. Schneider’s comments illustrate that ecosomatics can make an important intervention, even in Native and Indigenous studies discourses, by underscoring how bodies and bodily movements can vitally contribute to “the restoration of Indigenous land relationships.” –Tria Blu Wakpa, What Native American Dance Does and the Stakes of Ecosomatics

_ _ _ _ _

Death

Disturbance, disaster, and death often travel together. Their companions are grief and mourning.

“Grief is praise, because it is the natural way love honors what it misses.” -Martin Prechtel, The Smell of Rain on Dust

Every ethnic group, religion, and culture has their own unique prescribed set of movements, ceremonies, songs, or other activities that must be performed after a death. These can be rituals for the deceased and/or for the living. To survey the global variety of choreographies relevant to this topic would probably take years.

For now, what remains of your cultural context, as regards death and mourning? Do you know each movement, each phrase? Is it unchoreographed? Or, like a “score” in dance terms, has some fixed landmarks, but plenty of room for improvisation?

Have you been thrown unwillingly into a dance without knowing the steps?

Do you remember what shapes your body has inhabited in the moments of tending to the death of another being, whether human or non-human, or a place? How long did you linger in each pose? What was the landscape of your inner thoughts, feelings, and dreams?

Think of all the deaths and births, across the spectrum of species, a place has witnessed, held, provided for, and remembers. In the span of a single day, how many individuals died in these woods, and how many were born? How were they grieved, and for how long? How does their passing leave an absence, how quickly do the materials of their body become earth again? How many unmarked graves have I passed today?

“Is life on earth metamorphosing, and is this seeming ravaging of the earth what apoptosis feels like inside the organism? Is life on earth selectively shutting down portions of itself in order to increase its chances of survival through life-threatening conditions we are only dimly aware of?…Is life on earth dying like an old man in his sleep, his body’s memories unraveling moment by moment?” –Ben Kessler, Rivers of Wind: Reflections on Nature and Language

_ _ _ _ _

Possibility, Imagination, Propagation

“In order to achieve this radical reordering, the body must first be disorganized. For the Japanese avant-garde in the 1960s, including Hijikata and his comrades in his DANCE EXPERIENCES, the first order of the day was to break societal norms and reject the bodily habits instilled by the rapidly industrializing modern Japanese nation. In this sense, disorganization called for a kind of “canceling [of] the self” (Baird 2012, 160), in which the dancer must give up their social and cultural being and challenge the social and cultural patterns (SU-EN 2003, 70) in which they have been subtly and deeply trained. Disturbance is a key factor in this ongoing struggle.” -Rosemary Candelario, Butoh Ecologies: Dance Practice as Training for a New Relationship with the Environment

In the gaps of light and bare earth opened up in the course of disturbance events, what trajectory will prevail? Culturally and ecologically, where are we going? The possibilities that we can dream or imagine depend upon how imagining itself is understood.

“Imagination, in its ecological sense, is the cognitive and spiritual condition of entwining with local and cosmological intelligences. Indeed, imagination is the spiritual medium of those powers that engage humans without humans being the prime movers of the act. Imagination did not become a quality of a singularly human mind until mind severed itself from landscape and the depths of time. For the Haudenosaunee, imagination possesses no prehistory. Imagination became something other than what it is when mind went solo into Cartesian waters and lost sight of mythological shores. When mind decided against validating the psychoactive encounter with Creation’s multiple dimensions, mind compensated for the loss with belief systems that worked from a false legitimacy. Imagination subsequently became a wrecking yard collecting the parts that fell out of the old equations.

…just as stories that want to be told find their tellers, the expression across species diversifies itself by thinking in the consciousness of all beings. One need only keep company with coyotes, wolves, or foxes to know this with certainty. Yet as the experience of biodiversity wanes, so wanes the capacity for thinking with nature and beyond species-specific consciousness.” -Joe Sheridan and Roronhiakewen “He Clears the Sky” Dan Longboat, The Haudenosaunee Imagination and the Ecology of the Sacred

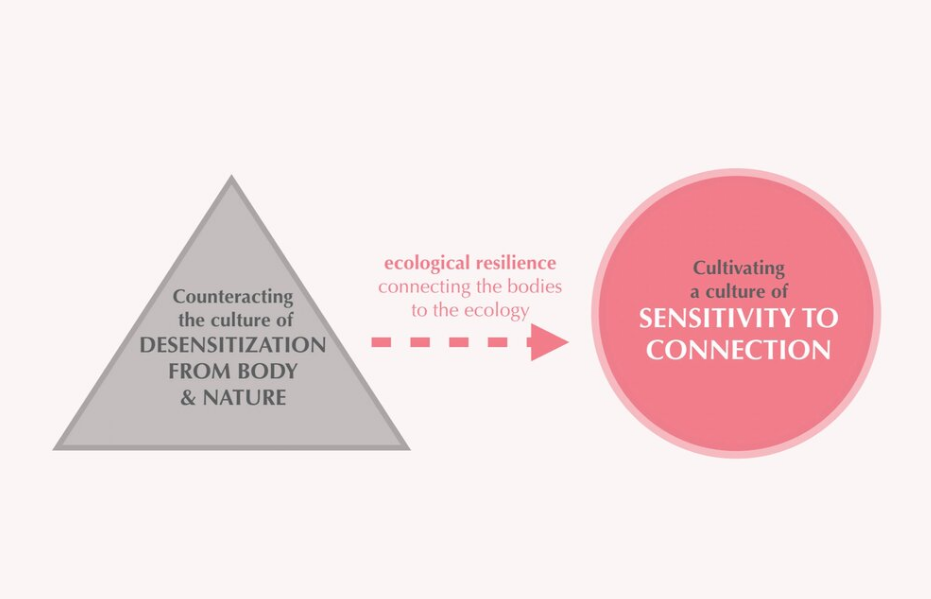

I am especially drawn to Butoh dance because the training often focuses on cultivating a porosity in the body. Through Butoh practices, the body is available, sensitive, and able to be moved by subtle natural forces and perhaps even the “local and cosmological intelligences” referenced above. If dancing is thinking, and “sensing is always at the interface of movings of a mindful body,” as Maxine Sheets-Johnstone described in Thinking in Movement, then the capacity to think with nature, as Longboat and Sheridan have described, is also the capacity to move with nature, beyond species-specific consciousness. As Lani Weissbach writes in Decentering the Human through Butoh,

“The act of becoming that is unique to butoh is also an act of decentering the human, which is a radical paradigm shift in how we can experience ourselves in an interconnected web of life. To me, decentering the human means that I consciously let go of my attachment to myself and open the lens of my conscious and somatic presence to include and be moved by the wider world around me. In this receptive, fluid, and permeable state, I am not passive or in any way denying that there is a self that is present. Rather, I temporarily expand this sense of self to include the world around me. In essence, I become more-than-human.

This process of becoming is supported by another butoh method for decentering—the practice of literally taking oneself off-balance, often in barely perceptible shifts in one’s position. Using micromovements to take the body into asymmetry allows the dancer to attune to more subtle internal and external sensations and stimuli, which contributes to the sense of detaching from one’s human form.”

I resonate with this description, and also wonder about entertaining a phrasing version like: “The more-than-human becomes me.” Dancing in landscapes, whether in the woods full of falling Ashes or at the rubble zone of the demolished shopping mall, I invite the place and their inhabitants to move or use my body. We move for the practical means of materially tending a place, to act as a catalyst or coordinator for other processes, or for other integrative, playful, or spiritual reasons beyond what is immediately apparent. We are vessels all the time, even with seemingly-conscious will and agency. For example, when there is a particular plant I become enamored with, I desire to propagate them and ensure habitats for them. Why am I drawn to them? Why do I feel so compelled to understand them? Is their spirit reaching out to me, cultivating a connection, knowing I have nimble hands that are ready, able, and willing to help their seeds and roots move, spread, and thrive? Medicinal plants have had close symbiotic relationships with their humans for as long as anyone can remember. This is not to erase the agency of the human, but to reintegrate complexity and reconsider the locus of choice within a complicated ecosystem of influence. Or perhaps it’s simpler yet: as my partner describes, “When you drink the water from the place, you become the place, or the place becomes you. The groundwater molecules are absorbed, flow in your veins, become your own body. Over time an amalgamation of selves is possible.” The porosity described in Butoh practices is probably much more ubiquitous than we realize. In quite material ways of day-to-day living, the sacred intertwines with the mundane.

Choreography of Enriching a Seedbank:

Collect ripe seeds from native plants throughout the year.

Be sure to collect them from many different locations nearby

(To ensure genetic diversity)

(Ensure ethical harvest practices)

Scatter the seeds in fall and spring, ideally near existing populations of the same species

who may otherwise be dwindling in their genetic resilience.

You might also intentionally scatter them in areas of disturbance or cleared ground.

Alternatively, spend the day dancing in a least three different locations,

where several plants are noticeably seeding;

Wear fuzzy clothes so the seeds stick to you and travel with you between the locations.

Either way, share the seeds with others, so they spread and intermingle far and wide.

If even just one of these species makes it through the extinction portal,

the dance may well have been worth it.

Our bodies and hands are vessels, carrying, transporting; a mammalian extension of wind or water.

Ideas are seeds, too: may our collective imagination lead to an enriched seedbank, carrying diverse lineages of liberatory vision through many generations

As we think about the processes of ecological disturbance events, let us consider the minds that design them, drive them, and envision and enact possible futures in the wake of those disturbances. Which ones are driven by human minds that deny the possibility of amalgamation with other beings, seeing them as inferior, beneath notice, simply resources to be exploited? Which are driven by an entanglement of multi-species minds?

Which disturbance events are by design and which are accidental, or perhaps inevitable? What disturbance events, do we participate in on a daily basis? What does it mean, in terms of embodiment practices, to become “porous” and available to be moved by ecological processes that are full of dynamic change, and at times, catastrophe or extinction? Which aspects of ecological succession in the places that we inhabit have we already “amalgamated” with? Who do we choose to conspire with when we imagine the future?

_ _ _ _ _

Eclipse

On the ridgetop, perhaps where the Peregrine Falcons nest, Table Mountain Pine and remnant American Chestnut live in privacy and hermitage, spared from logging operations and real estate development on their steep and rocky ledges. Perched there, high in the mountains, will you tell us what you see coming, and what you ask of us?

_ _ _ _ _