This article was originally published on EFTE-Applied Research and Education

Nature is life, and nature is rhythm. Co-evolved and co-evolving with plants, animals, fungi, bacteria, weather, water, and all organic elements, humans are inherently part of the symphony of rhythms and relationships.

It’s no surprise, then, that a number of recent scientific studies tackle the problems of modern indoor-centric life and support the assertion that spending a significant amount of time outdoors improves wellbeing. A robust study in 2019 found that exactly two hours of time in nature (outdoor environments like woodlands, beaches, parks, etc.) per week improved health and wellbeing, as reported by the participants. Jim Robbins recently reported on this topic and included findings that time in nature can “lower blood pressure and stress hormone levels, enhance immune function, reduce anxiety, and improve mood.” A 2017 article in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health elucidates how the many benefits of nature experience are most likely related to the variety of sensory inputs combined with particular microbes and chemical compounds our bodies contact and absorb. While vision can be an important sense overall, the article affirms that total lived experiences in the environment full of sounds, smells, tastes, and tactile opportunity are crucial for wellbeing.

Phytoncides, organic compounds usually emitted by plants for defensive purposes, “permeate the air in natural environments and are ingested by visitors [or inhabitants]…They are a popular topic of study in Japan, and widely believed to contribute to benefits experienced during nature walks known as ‘shinrin-yoku,’ or ‘forest-bathing.’” Several phytoncides have been found to be antimicrobial, to increase immune system activity, and to decrease stress.

Air ions, charged particles resulting from radiation, cosmic rays, solar waves, waterfalls, thunder, and UV light, are “particularly abundant in natural places…and they have been suggested as one of the potential mechanisms for the physiological and mood benefits of natural places.” The negative air ions found outdoors “stabilize mood and increase vigor, friendliness, and ease of concentration,” while indoor spaces devoid of the ions are associated with depression.

And of course, we must remember that many of the hundred trillion bacteria in our bodies come from soil, water, animal feces, and spores. The “gut microbiota” is crucial for nervous system functioning, and decreased exposure due to a sanitized indoor lifestyle hinders our ability to benefit from those relationships.

Deepening Relationship: Co-regulation

The scientific findings on nature and wellbeing are amplified when we invite in dialogue from psychology and the arts. As someone engaged in body-based healing and therapy, I’ve been studying the Polyvagal Theory, created by Dr. Stephen Porges and referred to by Deb Dana as “the science of feeling safe enough to take the risks of living.” Polyvagal Theory works with the commonly known idea of “fight, flight, or freeze” in regards to human behavior and nervous system activation, and it adds another category: social engagement. The states of nervous system activation could be envisioned as a ladder–if something has signaled to us that our life is in major danger or that we are trapped, we shut down and freeze. That’s the bottom of the ladder, and the oldest part of our nervous system known as the Dorsal Vagus. When we mobilize in order to fight or run away from the stressor or threat, we’re in our sympathetic nervous system. When we perceive safety, largely through the presence of healthy relationships, we enter into the newest part of our nervous system, the Ventral Vagus (VV). Here, at the top of the ladder, we are able to socially engage and communicate with a sense of curiosity. In order to move from shut down to VV, one needs to move through some sympathetic activation on the ladder.

Co-regulation is key for accessing VV energy. In cases of trauma, it can be difficult to self-regulate. Though it may also be difficult to establish enough trust to develop a healthy co-regulation relationship, that relationship built over time is crucial for regaining resilience within the nervous system. Co-regulation is actually a biological need that all humans have for reciprocal regulation; it’s the way our nervous systems talk to each other, connect, mirror, and help each other feel safe enough as we move through the various states of activation and relaxation. It’s for this reason that I love to see “community care” involved in any conversation about “self care.”

Essentially, the research on how nature time and health/wellness are interconnected mirrors the finding that spending time in nature helps people reconnect with the VV state. As described in the book Nature-based Therapy by Nevin Harper, Kathryn Rose, and David Segal, “Nature is filled with an abundance of flora and fauna that help engage people in the present moment and embodied exploration. [They] bring out curiosity in people and motivate a further connection with nature…Encounters with beings that can be climbed, tended, and taken in awe or wonder provide a powerful means to engage in the present moment and begin the process of acquainting [people] to their own nature, their own animal bodies, and specifically their mammalian nervous system.” In other words, outdoor environments stimulate curiosity, connection, wonder, and embodied presence that immediately bring us into a Ventral Vagal state.

In “Performing ecologies in a world in crisis,” (an editorial preface to Choreographic Practices) Robert Bingham references choreographer/performer/professor Merián Soto’s outdoor improvisational work Into the Woods: “She urges readers to ‘just go’ outside and feel the heartbeat of nature through their moving, sensing bodies.” To feel a heartbeat is, indeed, a somatic experience. In your own body, you might find that you are aware of your heartbeat and that the awareness is heightened through touch. Touch, colloquially referred to as “the mother of all senses,” is in many ways our most intimate sense and has the greatest co-regulating capabilities. What would it be like to touch the earth with the open intention of feeling the heartbeat of nature, of life itself? What would it be like to garden and grow food with that kind of touch? What would it be like to move through the world still in contact with that rhythm, to make decisions and develop habits from that place of felt-connectedness?

In terms of co-regulating with non-human creatures, we probably most readily understand it with animals, perhaps through relationships with pets. But I propose that even though plants don’t have a nervous system in exactly the way mammals do, we still enter into a dynamic, responsive relationship with them. Studies show that “plants evolved to have between 15 and 20 separate senses including human-like abilities for smell, taste, sight, touch and hearing.” Plants can remember, sense danger, respond with chemical alterations accordingly, and communicate information to their nearby communities. They’re especially intertwined with fungal communication networks. And there may be much more about their rich internal life that we haven’t scientifically explained yet. All this to say: our plant friends are very much alive, and they have a rhythm and intelligence that inevitably resonates in our bodies, helping to balance us as we grow closer to them. Perhaps we can co-regulate with them, just like we co-regulate with friends, partners, pets, or therapists.

Deepening Relationship: Reciprocity

As we grow closer to nature, spending more time outdoors, getting to know various species, becoming more and more intimate, we may find that we agree with Merián Soto when she asserts that “we are nature.” The authors of Nature-based Therapy agree, emphasizing that their approach to therapy involves supporting a reunion with nature as opposed to an extraction relationship in which humans take benefit from some “thing” that is separate from them. Importantly, the authors also note that outdoor experiences often include an element of risk. Nature isn’t always soothing or tranquil. And from their standpoint, accepting inherent risk is “both restorative and meaningfully disruptive (i.e. burdensome, tiring, challenging).” The risk and therefore inclusion and toning of quick-response survival mechanisms combined with the overall Ventral Vagal support as described earlier in this article actually helps create a more resilient nervous system.

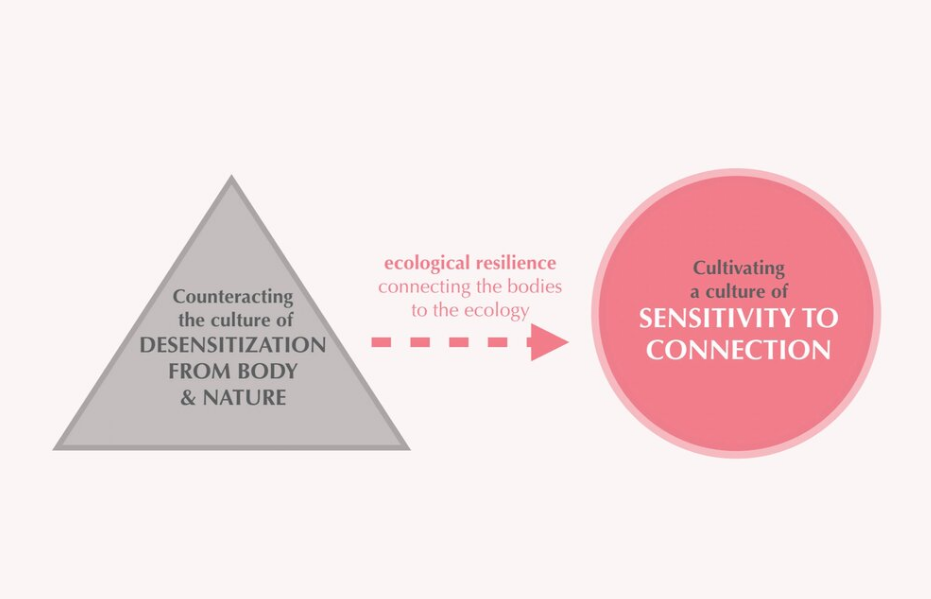

Robin Wall Kimmerer, whose environmental work is grounded in the knowledge systems of First Nations, sees human-plant relationships as that of “kin.” The view of being-family supports an attitude of gratitude and togetherness. Sondra Fraleigh beautifully writes that “as we move our senses out towards the world, and a sense of the world returns to us, there is folding reciprocal play in consciousness.” Reciprocity is real depth of relationship, and what is missing from so much of modern postcolonialist life. While I can appreciate the scientific studies about how being outside in “nature” (for just two hours a week!) improves human health, the studies also perpetuate the problematic view that nature is simply something beautiful/useful for us to feel better, and then we can go on back into the broken bifurcated system keeping us separate from our kin, and essentially, ourselves.

When we come into full reciprocity in relationships, we feel the ebbs and flows of giving and receiving. We feel the innate desire to take care of the earth arise within us. We recognize all the ways we are fed, and we wish to give back equally and frequently. We grieve loss of non-human kin the same way we grieve human loved ones. We ask what we can do to help and support in times of need. We are ready to respond in times of crisis, such as now. Whether the response is shifting the paradigm back to connection, supporting and ushering in political systems that will immediately create large-scale energy and environmental protection reform, supporting indigenous people and returning land to them, caring for regional plants through propagation and stewardship, seed saving, reforesting cleared lands, getting to know local ecology and species, learning wildlife rhythms and needs, taking fewer resources, fighting for regenerative growing practices rather than destructive industrial agriculture, offering material tokens of appreciation, or simply feeding a bird, or a bee, or dancing the spirit of a place— whatever the response, the embodied reciprocity is the heart of healing.